08.07.2025

Eye Tracking as a Window into Digital Addiction

by Mirta Ivanek, Product Manager

by Mirta Ivanek, Product Manager

In today’s hyperconnected world, the average person spends over 6 hours a day engaged with digital media1. While this connectivity has transformed how we work, learn, and communicate, it has also given rise to a pressing concern: digital addiction. As screen time rises, so does the urgency to understand the cognitive, behavioral, and psychological impacts of excessive digital engagement. One emerging method in this research frontier is eye tracking. This blog explores the phenomenon of digital addiction and how eye tracking is playing a crucial role in understanding and potentially mitigating it.

What is Digital Addiction?

Digital addiction, often referred to as problematic internet use or technology overuse, is characterized by compulsive engagement with digital devices – smartphones, social media, gaming platforms, or streaming services – often at the expense of mental health, productivity, and interpersonal relationships. Unlike traditional addictions (e.g., substance use), digital addiction is behavioral. However, it also shares core features such as tolerance, withdrawal symptoms, loss of control, and continued use despite harm2,3. The condition is gaining recognition: for example, gaming disorder has been officially included in the WHO’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11)4.

Neurological and Cognitive Effects of Excessive Screen Time

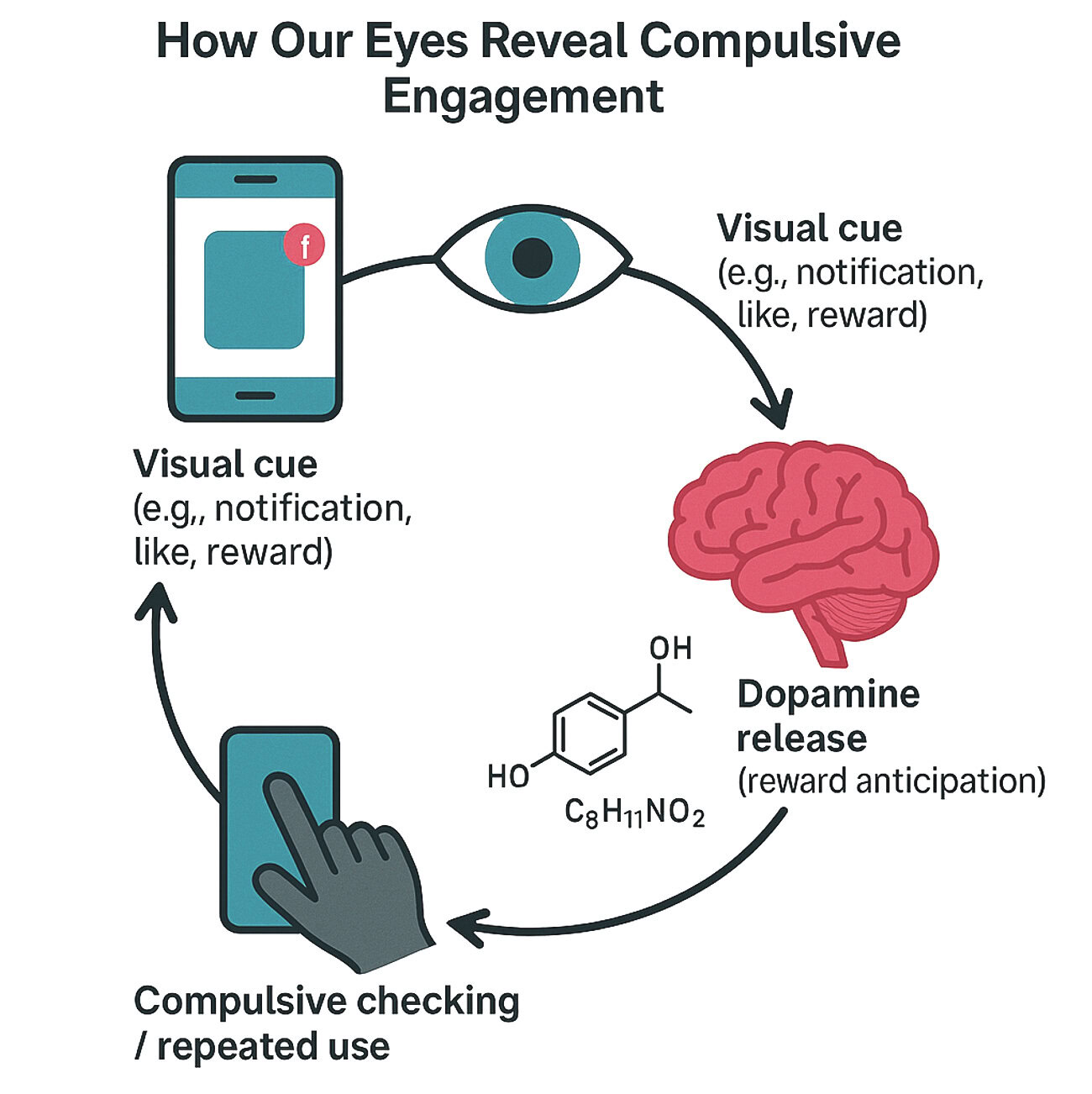

Neuroscientific research has linked excessive screen use to structural and functional changes in the brain, especially in the areas related to attention, impulse control, and reward processing5. Chronic screen exposure can alter dopaminergic reward systems, leading to compulsive behavior similar to other forms of addiction6.

From a cognitive standpoint, heavy digital multitasking has been associated with reduced attentional control, increased distractibility, and impaired working memory7. These deficits not only affect academic and work performance but can exacerbate the cycle of overuse.

The Role of Eye Tracking in Studying Digital Addiction

Eye tracking technology allows researchers to measure where, how long, and how frequently users look at certain elements on a screen. It captures metrics like:

- Fixation duration (how long a user looks at one point)

- Saccadic movements (rapid eye movements between fixations)

- Pupil dilation (indicator of cognitive load and emotional arousal)

- Gaze patterns (scanpaths or heatmaps of visual attention)

These metrics are invaluable for understanding how digital content captivates and potentially hijacks attention.

- Quantifying Attention and Engagement

Eye tracking helps determine which elements (e.g., social media notifications, game rewards) capture excessive attention. Research shows that individuals with problematic smartphone use spend disproportionally more time fixating on rewarding stimuli, such as “likes” or push notifications8.

- Monitoring Impulse and Distraction

In controlled experiments, eye tracking can reveal whether users are more prone to visual distraction when multitasking or exposed to tempting digital cues. This is especially useful for evaluating self-regulation in populations vulnerable to digital overuse, such as adolescents.

- Detecting Early Biomarkers of Addiction

Recent research suggests that gaze behavior patterns, as measured through eye tracking, may serve as early biomarkers for digital dependency. For example, one study found that Facebook users with higher addiction scores spent more time fixating on update-related areas of the interface like the Newsfeed, indicating a strong attentional bias toward new content9. Similarly, Chen et al. reported that short-form video users showing signs of addiction had more frequent and shorter fixations – suggesting difficulty maintain attention and a tendency for compulsive scanning10.

These findings highlight eye tracking metrics – such as fixation count, fixation duration, and saccadic frequency – as non-invasive, quantifiable indicators of early-stage digital addiction. People with smartphone or internet use disorders often display atypical oculomotor patterns, such as shortened fixations and increased saccadic movements, which reflect decreased cognitive control and heightened impulsivity. In the context of Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD), affected individuals make more errors during an anti-saccade task when exposed to gaming-related cues, suggesting impaired inhibitory control and attentional bias11.

- Designing Interventions

Eye tracking can inform the design of digital wellbeing tools. For example, adaptive user interfaces that detect gaze aversion or screen fatigue could offer break reminders, reduce notification frequency, or transition to grayscale mode to curb overuse.

A New Lens on Digital Addiction

Digital addiction is a growing public health concern, particularly among young people and heavy tech users. Addressing it requires a multi-dimensional approach, and eye tracking provides a uniquely powerful and data-rich method for observing how people engage with digital content in real time. By capturing subtle visual behaviors linked to attention, impulse control, and cognitive load, eye tracking enables early detection of problematic patterns before they escalate. As research and technology evolve, eye tracking could become an essential tool not just for diagnosing digital overuse but also for shaping more mindful digital design, informing interventions, and promoting healthier screen habits.

1

Meng, S.-Q., Cheng, J.-L., Li, Y.-Y., Yang, X.-Q., Zheng, J.-W., Chang, X.-W., Shi, Y., Chen, Y., Lu, L., Sun, Y., Bao, Y.-P., & Shi, J. (2022). Global prevalence of digital addiction in general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 92

2

Billieux,J., Maurage, P., Lopez-Fernandez,O., Kuss, D.J., & Griffiths, M.D. (2015). Can Disordered Mobile Phone Use Be Considered a Behavioral Addiction? An Update on Current Evidence and a Comprehension Model for Future Research. Curr Addict Rep, 2, 156-162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-015-0054-y

3

De-Sola Gutierrez, J., Rodriguez de Fonseca, F., & Rubio, G. (2016). Cell-Phone Addiction: A Review. Front. Psychiatry, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00175

4

World Health Organization. (2019). International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision (ICD-11). https://icd.who.int/

5

Dong, G., DeVito, E.E., Du, X., & Cui, Z. (2012). Impaired inhibitory control in ‘internet addiction disorder’: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 203(2-3), 153-158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pscychresns.2012.02.001

6

Kuss, D.J., Griffiths, M.D. (2012). Internet and gaming addiction: a systematic literature review of neuroimaging studies. Brain Sciences, 2(3):347-374. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci2030347

7

Ophir, E., Nass, C., & Wagner, A.D. (2009). Cognitive control in media multitaskers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(37), 15589-15587. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0903620106

8

Elhai, J.D., Yang, H., Fang, J., Bai, X., & Hall, B.J. (2020). Depression and anxiety symptoms are related to problematic smartphone use severity in Chinese young adults: Fear of missing out as a mediator. Addictive Behaviors, 101, 105962. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.04.020

9

Hussain, Z., Simonovic, B., Stupple, E.J.N., & Austin, M. (2019). Using Eye Tracking to Explore Facebook Use and Associations with Facebook Addiction, Mental Well-being, and Personality. Behav. Sci., 9(2). https://doi.org/10.3390/bs9020019

10

Chen, Y., Li, M., Guo, F., & Wang, X. (2022). The effect of short-form video addiction on users’ attention. Behaviour & Information Technology, 42(16), 2893-2910. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2022.2151512

11

Kim, M., Lee, T.H., Choi, J.-S., Kwak, Y.B., Hwang, W.J., Kim, T., Lee, J.Y., Kim, B.M., & Kwon, J.S. (2019). Dysfunctional attentional bias and inhibitory control during anti-saccade task in patients with internet gaming disorder: An eye tracking study. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry, 20:95:109717. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2019.109717